Historic buildings – vacant but not empty

By Lynda MacGibbon

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound …. The church was silent, but if I listened with my heart, I was certain I could hear voices singing, feet shuffling, the rustle of onion skin-thin pages turning.

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound …. The church was silent, but if I listened with my heart, I was certain I could hear voices singing, feet shuffling, the rustle of onion skin-thin pages turning.

In front of me, the arched window framed a view of a deep, blue river, leafy birch and deep green firs. It was a view capable of captivating the attention of the most pious of Sunday morning worshippers. Pity the poor preacher whose sermon dawdled too long past the 12 noon curfew.

Below me, the sanctuary of the church was empty on the day I was there, but as I turned from the window and leaned across the balcony railing, I could see pews filled with worshippers of days past. I could feel the scratchy wool of a Sunday-go-to-meeting suit, smell the light scent of soap-scrubbed skin. I wanted to fan myself against the cloistered heat of a summer service.

Do people leave imprints of their souls on well-loved buildings? I have no answer, of course, just a dreamy wish that there might be a degree of substance to the thought.

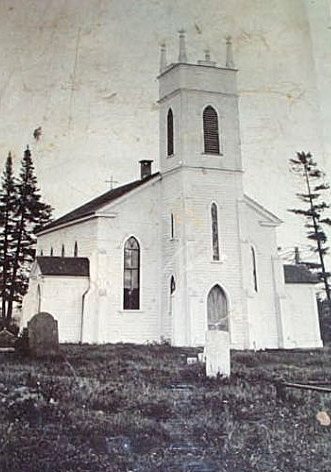

Such questions occur to me when I visit places like the Mira Ferry Church in Cape Breton. My great grandfather, Hector MacGibbon, was a trustee of the church, which sits on the banks of the river made famous by Allister MacGillivray’s Song for the Mira.

I visited the church last summer, took a few pictures and didn’t think much more about it until yesterday morning when I arrived at work to find a note on my desk from sisters Norma Harris and Joan Jardine. They grew up next door to Trinity Church in Blackville, the subject of reporter Cathryn Spence’s feature story in last Saturday’s newspaper. Old Trinity, as it’s known in the region around Miramichi, was recently sold to a new owner who moved the church to Oklahoma City.

It’s both a happy and a sad story. Happy because the church likely would have crumbled to the ground had it not been sold. Sad because a piece of Blackville has been removed forever from the landscape of the area.

It has not, however, disappeared from memory. This is what Norma and Joan wrote:

The church was like home to us as it was always open for anyone to drop in. Of course, we lived next door and we did just that. We would sit in the pews, trying to play the organ and doing other things, like cleaning up for Sunday services. We never missed going to Sunday School on Sunday …. Last year, my husband and I had the opportunity of storing the dismantled church, for Mike Gorman from Renovators Resource, in our back yard. Then, when it came time for the church to be moved to Oklahoma, my two sons with their trucks and flatbeds journeyed to Oklahoma City. It was sad to see it go, but maybe one day, my sister and I will get to see it once again and rekindle the many old memories we have.”

I hope Norma and Joan are able to make such a visit, and if not, perhaps their grandchildren or great grandchildren will. Such an opportunity, after all, is one of the amazing gifts offered by old buildings, particularly those open to the public.

My great grandfather’s home, a small white farmhouse, still stands just down the road from the Mira Ferry church. But the house hasn’t been in our family for many decades and it sits far back from the road, obscured by alders. I can’t go there, can’t walk across floorboards that bore his weight, or gaze from a window at a view he enjoyed.

At least, I can’t do such things from his house. But I can do it from another house, one he shared with neighbours, with extended family, with a Sunday morning preacher who might have gone on a little too long at times. It’s a house he shared with God, and where I’m certain he joined in singing the old hymn, Amazing Grace.

RELATED: Read the amazing story of Old Trinity’s move to America: Oklahoman Sisters Bring New Life to Old Trinity